Queer Camp: a Week Under the Rainbow Flag

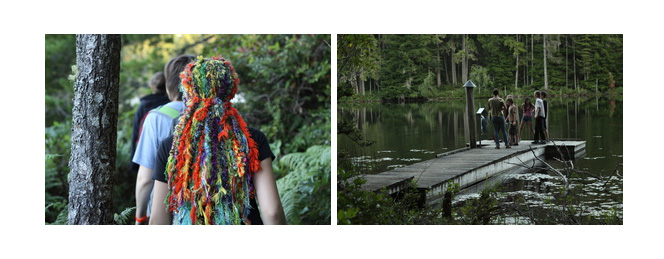

“Alright everyone,” a tall individual breaks into the large circle and presses some buttons on the stereo, “that’s enough with all of the music and dancing — the kitchen is almost done with a wonderful meal of pancakes and vegetarian bacon. It’s time for flag.” They cheer with excitement, then fall silent as ze raises zers hand limply to zers brow, behind which sits a thick ponytail of roughly seventy braids. Each contains a long piece of yarn which was woven into place, forming a sloppy rainbow.

“Assume the position!” We all copy zer, loosely saluting as a group of campers carry in two rainbow flags and work together to hoist them up a pole. Between them sits a hand painted canvas sheet with the words “Camp Ten Trees” lettered onto its center.

There are rainbows everywhere, as would be expected, considering the fact that it stands among a select number of camps that provide queer and trans* youth and children of queer families an affirming and supportive space to be themselves, whilst enjoying a traditional summer camp experience.

The camp, now in it’s 11th year of operation, holds two one week long sessions every year in the month of August; one for children of queer families, and one for queer and allied youth.

By the time we’ve finished eating our meal, it’s only eight o’clock and the cold, damp air of Washington’s Pacific rainforest has yet to absorb the sun’s warmth, but the chill that works its way into theme day costumes does little to slow the beginning of early morning activities and discussions.

“I tend to get into fights on Facebook a lot,” Says Jordan, 15, as she sits on a peeling bench with her social justice discussion group in an open-air cook shelter. “One of my guy friends posted a status that said, ‘I had a really gay day.’ I commented on it and said, ‘So your day was either super happy, or super fabulous; I think you mean you had a bad day.’” She pauses, waiting for the room’s laughter to subside, “It turned into a giant fight, and this gay guy was like ‘It doesn’t bother me, I don’t see why it would bother you.’ They didn’t understand and I got really mad.” She angles her head downward in frustration, revealing a large section of her curly hair that has been shaved close to the scalp.

An older counselor perches on one of the partial walls. His face is kind and possesses an inquisitive expression, “You know why a person, who is queer, might be uncomfortable with you calling someone out on something like that?” The question is directed at all of us, but we fail to produce an answer, “It’s probably because this guy has internalized the idea that it’s okay for heterosexuals to appropriate our identities and words and use them in a negative way, and that it’s best to just put up with it; you’re challenging that idea and that makes him uncomfortable, because if they go after you for trying to change things, they might come after him.”

As the week continues, you watch people change; they abandon walls they have built to protect themselves from the world. They try on new names and identities, and they begin to learn how it feels to not be the odd one out.

“Props please people,” Thumper, 30, skips between tables and hops gleefully onto the hearth in the back of the shelter we had used for our discussion earlier in the day and speaks loudly to grab our attention, “I’m super glad that so many of you know each other already, but we have some new people with us this week and we don’t want them to feel left out, so we’re going to do a little get to know you game, which I will demonstrate with Oak [a fellow counselor], and then we’re going to share what we learned.”

He waits for Oak, 21, to join him before he continues, “This is a partner get-to-know-you game where you learn some things about your partner and then introduce them to the group — I want you to find out their name, their PGPs and something they like to do for fun.” He puts extra emphasis on the word “fun”, giving it a suggestive feel that inspires a number of giggles and coy looks. Thumper grins widely at the crowd, “Fun things that are camp appropriate.”

“Hold on,” Oak sticks his finger in the air, “can someone explain PGPs for the group?” A hand shoots up and he nods, “How about you?”

“PGP stands for preferred gender pronouns, you say them when you introduce yourself so people don’t have to assume what you like to be referred to as.”

“Good explanation, thank you very much.” Oak motions for us to begin, and a few seconds later, we’re ready to share — any one want to go first?”

I point to the individual on my left, “This is John, he likes he-him pronouns, he’s 14, and for some reason he won’t fully explain, he really doesn’t like playing ping pong — something about a traumatic ping pong injury” He laughs and the multiple necklaces around his neck clink together softly as he adjusts his thick dreads, he then introduces me and the other sets of partners follow suit.

Thumper claps his hand softly and hops back onto the fireplace, “That was really good, but we’re not done, we have to put together a community agreement.” He pulls out some tape and color full sheets of paper, which he affixes to the mantle behind him and crouches next to with a marker in hand, “Go ahead and start yelling out some things that you need to feel safe here.”

“How about we ask for consent before we touch each other?”

“I think we can all agree to respect people’s pronouns.”

“Let’s assume that people have good intentions.”

As people call out, the papers slowly fill with guidelines we have discussed and agreed upon — we figure we’ve covered all the bases by the time a “no cannibalism rule” has been brought into the conversation.

Unlike a traditional camp environment where there are only cabins for people who identify as male and female, here there is an assortment of accommodations for girls, boys, trans* identified youth, and those who would prefer being in a coed environment. Campers can request to stay where they please without question, and should they feel another area of camp would be more appropriate once they arrive, arrangements can be made to switch.

While an intentional community of queer and allied persons plays a large role in making the space welcoming and affirming for queer youth, the little things that the camp has done in the nature of inclusion make a world of difference.

Here, all of the bathrooms are gender inclusive as to embrace trans* identities; people ask for pronouns as to avoid making assumptions; camp songs are changed to include queer and poly relationships; campers can choose whether they would or wouldn’t like to cover their chests while swimming, regardless of their gender identity or body type; and an effort is being made to rename parts of camp that had been given names appropriated from indigenous cultures.

Camp Ten Trees, and other organizations like it, present themselves as models of inclusion to be replicated by other organizations operating with majority bases. Minority individuals are faced with the reality that the de facto state of any space is one of marginalization and hostility, but by examining the world from an alternate viewpoints in order to identify and remedy issues that they may encounter, atmospheres that were once exclusionary can be made to be supportive and affirming.

-Alex Sennello